This website uses cookies to improve user experience.

Read more: Terms and conditions

Quiz: Does This Headline Tell It All?

Headlines and Manipulated Visuals

The purpose of a headline is to grab your attention and make you click on the link, buy the newspaper, or read the story. Sometimes the intent to get your attention might be strong enough for an outlet to decide that an exaggerated headline is a worthy tradeoff. Manipulated photos and videos are also sometimes used to amplify the emotional impact. Learn to recognize sensationalist headlines and the ways pictures can be distorted.

Manipulated Photos – Watch Out!

According to AFP Factcheck, “Tens of thousands of people shared a tweet of two [side-by-side] photos from the 2018 anti-government ‘yellow vest’ protests in Paris, captioned ‘Perspective matters.’”

Although the comparison indeed attempts to show how camera angles and image composition can be used in the news media to dramatize an otherwise minor event, the two photos in question here are themselves manipulating readers. The photos were actually taken at different times and in different places, not the yellow vest protests.

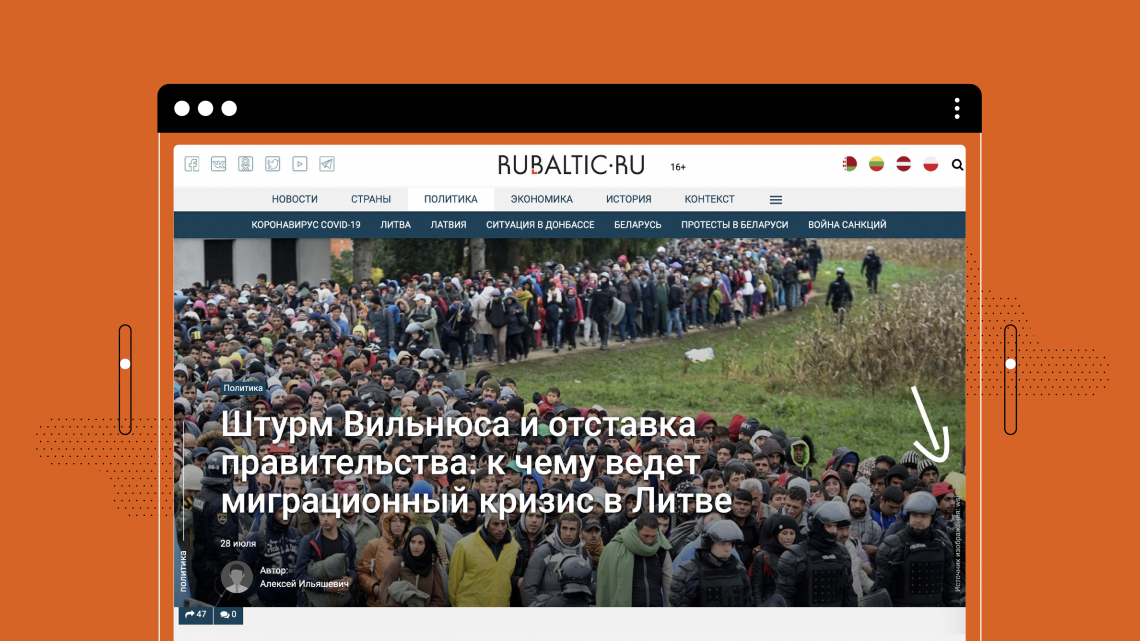

These manipulations are frequently spread in the Baltics, too. For example, the site rubaltic.ru posted an article on 2021 migration crisis in Lithuania using a photo of a massive crowd of people lining up. The photo was actually taken many years ago, and not in Lithuania.

Sensitive topics likely to cause strong emotions, like migration crises, usually inspire a lot of manipulators on social media too. For example, a manipulated screenshot from the news site 15min.lt was posted on Facebook. The faked screenshot gave the impression that the outlet had published an article saying that Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Gabrielius Landsbergis, proposed to forcibly house migrants in the houses and garages of Lithuanian residents.

A case in point – a lot of misleading content was also shared about the refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine. Fact-checkers all over Baltics saw cases where old photos and video footage was used to demean refugees (here are examples from Latvia and Lithuania).

Sometimes quality media also use images from other events to illustrate the text (like stock photos). Therefore, it is important to read the captions and see the source of the image to understand whether it depicts the event in question or if it’s just illustrative.

There are three types of photo manipulation:

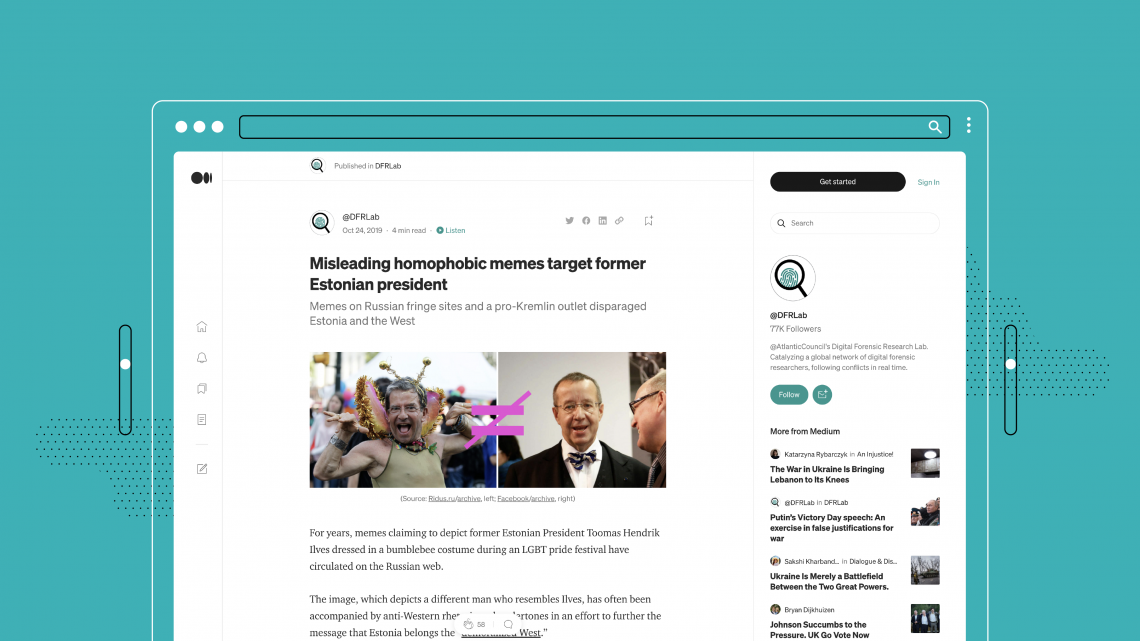

- A real photo of a place or person presented as an image of an entirely different place or person.

For example, memes claiming to depict the former Estonian President, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, dressed up in a bumblebee costume for a LGBTQ+ pride parade in Buenos Aires have been circulating for years. While the photos are real, the person depicted in the images is not Ilves.

Similarly, videos are decontextualized and reused for social media manipulation too. For example, thousands of people in Latvia shared a video that appeared to depict several body bags, with one person in a bag actually alive and smoking. Social media users republished it, adding captions that the video showed how photos of people who have died of Covid-19 are staged. In reality, it was a fragment of a behind-the-scenes clip from the filming of a music video in Russia.

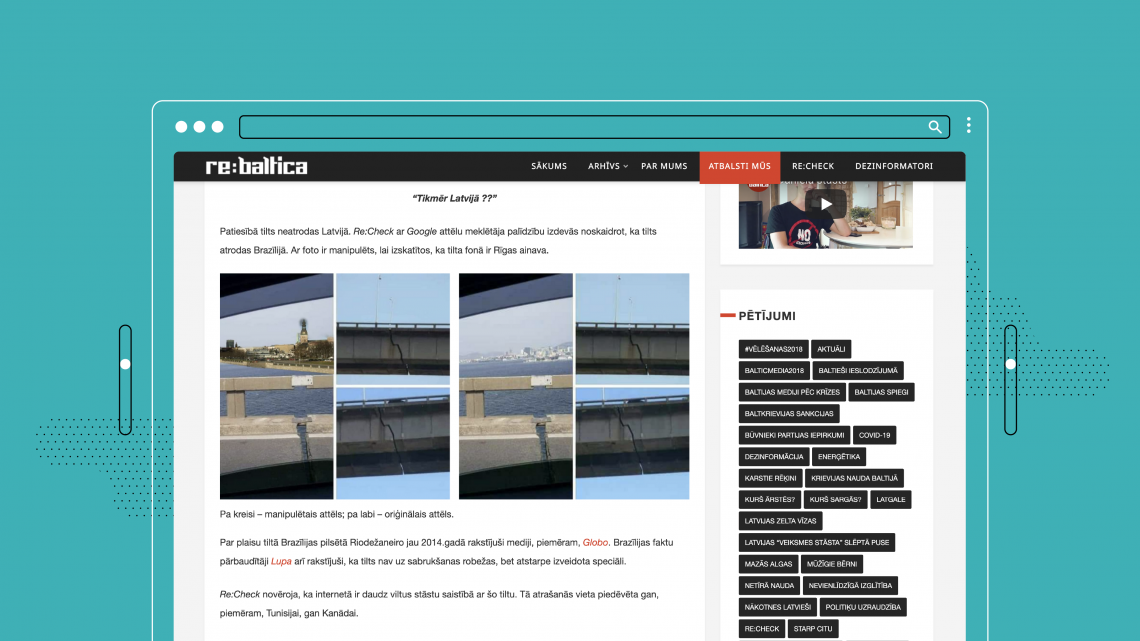

- Doctored photos altered in a graphics editor (like Photoshop) to add or remove some elements.

Social media users in Latvia were sharing an image that depicted a bridge with a large crack in it. The background of the bridge was edited to make it appear to be taken in Riga. Latvian journalists revealed that, in reality, the original photo was taken in Brazil and had been used in several countries, including Tunisia and Canada, to criticize local governments or municipalities.

- Cropped photos that show just part of an image out of context.

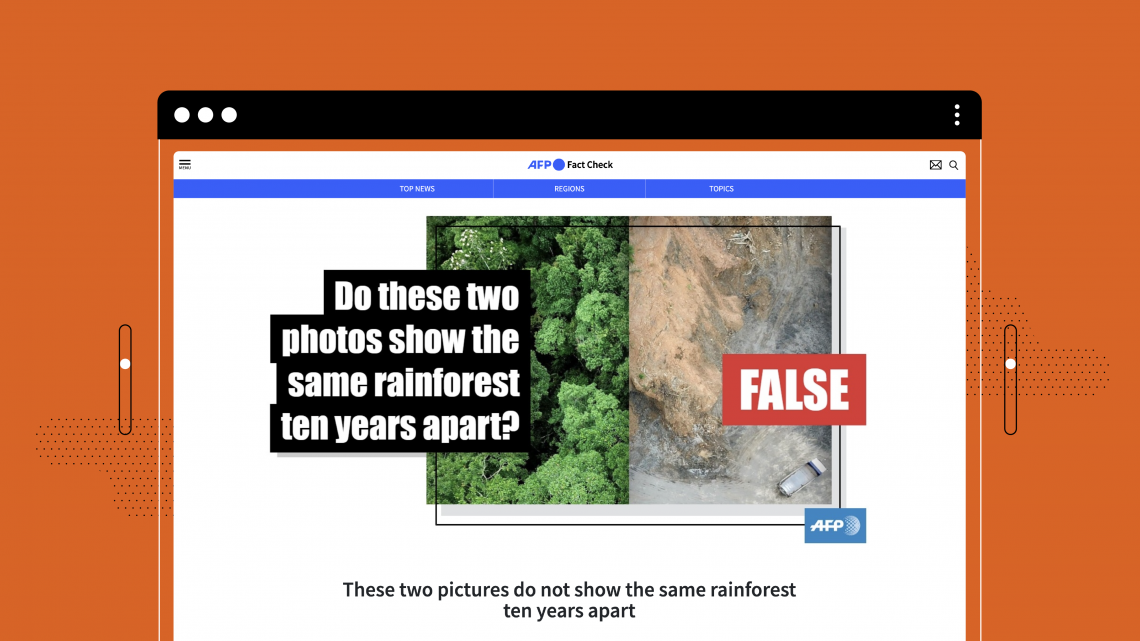

World Wildlife Fund – Pakistan published an image on Instagram supposedly comparing deforestation in Malaysian rainforests ten years apart. As fact-checkers from AFP revealed, both parts were actually from the same image taken in 2018.

Always question sensational headlines and watch out for outrageous photos. There’s a lot of these headlines in traditional media, as well as manipulated photos and dishonest captions on social media. Don’t let them mislead you.

Deepfakes and Cheapfakes

If you want to know more about detection of deepfakes, read this article and check your skills with this test.

Bots and Trolls

Not everyone on social media who shares posts, likes, and comments is a real person. Learn the difference between bots and trolls, and how to spot them.

Life Hacks: How to Detect Bots and Trolls

These days, social media is like a distorting mirror. It can help create or spread an illusion that someone is popular or an opinion leader. Likes and shares, sought after by many social media users, have become a tool to increase the visibility of manipulated news content and attack certain people, institutions, and ideas. Bots and trolls are often involved.

“Bots”, short for “robots,” pretend to be real people, but rather are anonymous, artificial identities coordinated by someone who does not want to disclose their real name or intentions. Not all bots are bad. For example, there are bots that post poetry or inspirational quotes. But bots can also be used to amplify certain political ideas and to manipulate others.

In addition to bots, there are trolls. Trolls are real people operating online profiles, whereas bots tend to be automated or otherwise programmed. Trolls aim to cause or provoke certain emotions, usually anger, and to maintain a degree of ongoing visibility and discussion online.

Trolls can be:

- Contractors hired to spark discussions

- Ideological warriors doing it for free and for their own motives

- Normal people—we all sometimes get caught up in a hot discussion in the comments section and start defending our opinions, deliberately stirring the emotions of others

Bots are capable only of primitive chatting, while trolls can provide complex arguments.

To spot bots among friends or page followers, try out these tools:

- Twitter Audit takes up to 5000 Twitter account followers and calculates a score for each follower—likelihood of being an authentic follower or not.

- Botometer determines the likelihood of an account on Twitter being run by a bot. Remember that this automated tool can make mistakes too (especially in languages other than English), but it can be one extra warning to make you more cautious. The creators of this tool have made another to help detect coordinated campaigns. Read more about it here.

- Account Analysis App can help you evaluate Twitter accounts. For example, it shows you the times of the day when a user posts most frequently. If their schedule looks odd, it can suggest that someone, for example, could be tweeting from another time zone than they claim. Also, a real human being cannot tweet intensively at all hours – people need to sleep. This tool also shows what languages an account uses in their tweets, which users they interact with the most, and which websites they refer to.

- Test your ability to detect GAN images created by machine learning by seeing if you can spot the difference between real or fake images. To explore a world of entirely fake images, as well as to see if you can spot tell-tale signs of them being computer-generated, visit This Person Does Not Exist.

Be wary of people you are friends with or follow on social media who you do not know in real life. If you see someone fanning the flames in the comments section, it’s often best to just stay away, because you may be dealing with a bot or a professional troll.

Quiz: Evaluate the Sources

Fake Expert Opinion

Fake photos and fake accounts are not the only ways to distort information. Sometimes both traditional media and social media users use fake experts, both accidentally and on purpose.

You can find someone claiming almost anything on the internet. However, the role of a journalist is to publish verified information and to be transparent about where the information is from. Some outlets try to sidestep this rule by attributing statements to fake experts to give unverified or manipulative content a veneer of legitimacy. The range of what this can mean is quite broad – starting from people who don’t exist at all to people who do not have the background to be called an expert on the subject.

A search of the expert’s or institution’s name online might reveal there are few internet records of them. So-called experts might not represent reputable institutions but come from tiny organizations that are driven by an individual or group’s political agenda.

There are a few telltale signs that could make you suspicious and start your investigation, like a vague description of why the person is included as an expert (for example, no organizations they represent are mentioned), an especially controversial topic, or an unfamiliar media outlet or social media user publishing the opinion.

For example, Rossiiskaya Gazeta published an interview with Einars Graudins, a Latvian politician. He was introduced as a Latvian human rights activist who, along with a group of experts from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), visited mass burial sites in a military conflict area in Ukraine. The man claimed that 400 bodies were discovered buried near Donetsk. Meanwhile, RIA Novosti and Vesti.ru presented the man as an OSCE expert. The OSCE later issued a statement that there was no such expert on its monitoring mission in Ukraine.

More recently, a network of 500 accounts affiliated with China were removed from Facebook for promoting the claims of a fake biologist from Switzerland named Wilson Edwards. Edwards, who does not actually exist, was used to claim that the US was meddling in efforts to find the origins of Covid-19. His statements were then re-published on Chinese state media.

If you can, check the expert’s background on the internet. Here are some things to take note of:

- Their experience as an expert: where have they worked and for how long? Can you find their resume?

– If someone is a reputable expert, it is likely that other media outlets have also used them as a source or they have written articles in different outlets themselves.

– Academic books, textbooks, and articles written by them, as well as the number of citations – the number of times other experts reference their findings in other articles and books. You can find this information, for example, on scholar.google.com. When you search for the name of the expert, you can see if they have written about the topic and how many others have found what they said useful enough to cite it.

– The reputation of the organization they represent: do they appear to be recognized by others for their knowledge or expertise? For example, are they invited to various conferences, discussions, and other speaking events? Is their name tied to any scandals that have been reported in the media?

Advertorials and Native Ads

The media must maintain a healthy balance between their commercial interests and observing journalistic standards. Media outlets are supposed to clearly label any advertising that is published. Also, journalists are not allowed to receive money from their sources for publishing something. Sometimes these concepts are mixed, ethical rules are violated, and, as a result, the media consumer receives an advertorial — an advertisement disguised as journalistic material.

Advertorials, a combination of advertisement and editorial (or an opinion article), can distort important issues and events. For example, a newspaper might be paid by a health supplement company to publish a story about the amazing health benefits of a new vitamin supplement, disguising it as one of several other stories that were selected by the editors.

Advertorials can deceive readers and viewers because people are generally more confident in journalistic materials than in advertisements or comments on social media. It is important to be aware of this possibility.

How to recognize an advertorial:

- Does the material have a strong focus on one particular product instead of an issue? For example, if you read an magazine article that repeatedly mentions a particular ointment to relieve back pain instead of providing more general information with several possible solutions, this is a strong signal that something is wrong.

- Is the material published without any reference to a place or time and is it hard to understand the relevance?

- Journalistic standards dictate a need to provide a variety of opinions. If the material is sharply positive or negative, it can be a sign of an advertorial.

- Material without authorship: journalists often don’t want to put their names under paid materials, so these materials are published without a signature or under a pseudonym. If the material seems suspicious, try to find other work from this author on the website or in the newspaper. You can also copy and paste or transcribe parts to run an internet search and see if the exact same information was published elsewhere.

Another form of advertising that looks a lot like a journalistic article is called a “native ad.” These articles often appear to be news, but an advertiser has paid to include some information, like a quote from a particular person who spreads commercial messages, while maintaining the appearance of not pushing a product. It makes the advertising elements in the article even harder to distinguish from the work of a journalist. The Society of Professional Journalists’ ethics code makes it clear that media outlets should “distinguish news from advertising and shun hybrids that blur the lines between the two.” However, these articles are published even in very prominent, world-famous outlets like The New York Times. Readers should be very attentive to various labels that can be used to describe this practice, like “native ad,” “sponsored content,” and “produced in cooperation with [company name].”

Manipulation of the Original Source

Imagine a situation where one person says it’s raining outside, and the other denies it. What would you believe? No need to guess, just look out the window and see for yourself!

This is what we call checking the primary source, which means going straight to the original source of information. When it comes to checking information on traditional or social media, it takes a bit more than just having a quick look out the window, but it’s a useful thing to learn to do.

First-hand or primary sources to check information may include:

- Official press releases from government and judicial bodies, local authorities, and international organizations

- Transcripts from meetings

- Full video footage of an event

- Official letters, appeals, and requests for information

- Official documents and contracts

- Direct, on-scene news reports (without editorializing/commentary)

- An organization’s official website

- People directly involved in the event, including eyewitnesses

Keep in mind that every outlet has its own editorial policy, target audience, and approach to newsgathering, and its own interests can depend on those of its owner. These elements can affect the topics the outlet chooses to cover and the angle it takes in its coverage. Social media users also have their own reasons for publishing or sharing certain information – although some post things without much thinking, others consciously post controversial things to grow their recognizability. Therefore, it often can be valuable to check the sources indicated in the material or look for the original source.

Often, journalists rely on other media for information that is relevant to a given story. Professional and honest media will link to or verbally credit these primary sources with phrases like “as reported by Postimees,” or “according to news agency LETA.” In online formats, they will usually provide a hyperlink for readers to be able to see the original source.

Note that sometimes it may be necessary to investigate further, as one cited source of information may have found that information from yet another source! Use Google or another search engine and keep searching until you are confident you have identified the original source of the information.

When something extraordinary happens, many media outlets are likely to report it, interview eyewitnesses and collect first-hand recordings (e.g. cell phone videos). So, if you are reading about an event that seems truly remarkable, yet after a few hours of searching you are still unable to find other photos or footage from the scene or other corroborating evidence, you may want to treat the information with a dose of healthy skepticism and not share it further.

Sometimes, news outlets publish information citing anonymous sources. This can happen for a number of legitimate reasons, most often out of concern for personal safety or as a result someone not being authorized to speak publicly on an issue, while those who are authorized may not want to be truthful. Even when done for legitimate reasons, information from unnamed or anonymous sources cannot be verified. In such cases, consider whether the reason given for the anonymity makes sense in the context of the story.

What should you look for during a publication background check?

As discussed previously, there is a lot of false, manipulative, and misleading information on social media, therefore you need to apply a lot of scrutiny before you share or believe something.

Ask yourself these questions before sharing or liking the post:

Fact-Checking

Fact-checkers are journalists who examine statements made by others and try to answer questions such as:

- Who made the claim? Do they have the expertise and information to know that?

- What evidence and sources did they provide to back up their claim? Does the source actually say what they claim it does?

- What are other sources saying?

A lot of the answers are acquired through interviews with experts, information requests to public institutions, and other tools often not easily available to the general public. However, there are some tools and methods everyone can and should use to evaluate information before they spread it further. Let’s learn about some of them!

The first thing you should do if you want to check information is read it carefully just like we have discussed previously. Remember, an article might get a lot of shares because of an oversimplified or sensationalistic headline but the full article might show more nuance and sometimes even contradict the headline!

Does the author explain what their sources are? If links to other sources are provided, read them. People who spread misinformation frequently add sources that, when read in full, add vital context that can completely change the meaning of a piece of information.

Case Study: Deaths After the Covid-19 Vaccine

Remember to check the information with other sources. For example, if you want to check information on a particular health risk that might be caused by a vaccine, see if the medicines agency of your country has said anything about it. Has the World Health Organization, European Medicines Agency, or the US’ Center for Disease Control and Prevention? These organizations were created to inform and update people about different health risks and often debunk popular myths on their websites. If the European Medicines Agency says that a piece of information isn’t true, is it very likely that Lukas from Klaipėda who often shares scandalous information on Instagram would know better? If you’re left unsure, it’s always better to take more time, look for other sources and see how events develop in time rather than sharing information that could harm someone. Care before you share!

Similarly with other topics – think of the institutions, research centers, and NGOs that work in the field and might have some more information on it. Can you find any news stories about the topic?

Google like a pro!

Here are some ways you can better explain to Google what you need in order to get better search results.

- Add quotes if you want the search results to only show the exact phrase. For example, type “Steve Jobs” if you are looking for information on the co-founder of Apple and don’t want to see unrelated information like job openings.

- Insert the minus sign “-” in front of the phrase you want to exclude. The query “jobs -steve” will show you information on jobs but not on Steve Jobs.

- Add “site:example.com” if you want to search for something on a specific website. For example, include “site:news.err.ee Steve Jobs” if you want to know if the website of the Estonian Public Broadcasting has ever mentioned Steve Jobs.

- Add “before:YYYY-MM-DD” and/or “after:YYYY-MM-DD” if you are looking for content from a specific time period. For example, “Krišjānis Kariņš after:2021-09-01 before:2021-10-01 site:delfi.lv” will show you Delfi.lv news stories between the 1st of September to the 1st of October 2021 where Krišjānis Kariņš, the Latvian prime minister at that time, is mentioned.

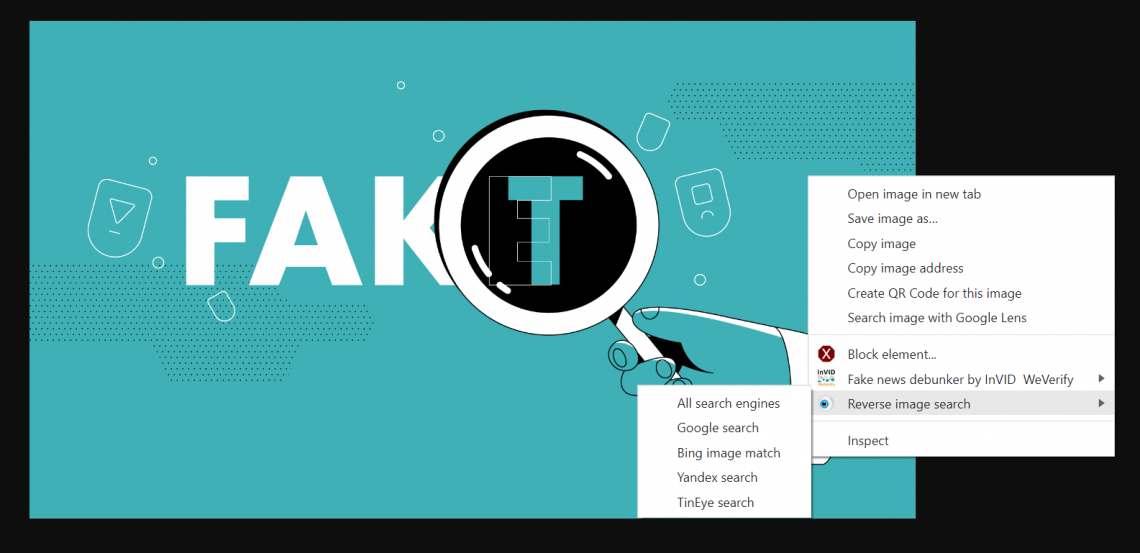

Check if the image on social media has been uploaded another time and in another context. There are a couple of browser extensions that can make image search fast and easy. If you add either RevEye (Chrome; Firefox) or InVid (Chrome and Firefox) extensions to your browser, you can look for the image on several reverse image search engines by simply doing a right click on it.

Alternatively, there are several reverse search image engines you can use (and often it’s useful to check a few) – Google, TinEye, Bing, Yandex. Note that Yandex is considered unsafe to use from a privacy perspective.

For additional analysis of an image, you can use Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer or Metadata2go that sometimes can reveal the device and time when the image was created or if it has been modified (an important caveat is that a lot of social media clear images from metadata). FotoForensics can show spots where an image has been edited. It can sometimes help you reveal cases of photo manipulation.

Videos are harder to analyze. There are no reverse video searches, however, you can reverse search the thumbnail image or make some screenshots of the video and then reverse search those. InVid can be helpful with video analysis too – it can select keyframes of the video for you. This video verification tool developed by Amnesty International can help get more information on YouTube videos.

This tutorial by AFP also shows the basics of how fact-checkers verify images and videos.

Other useful tools

Whois.com search can reveal some information about a domain and their holder.

Wayback Machine allows you to see the historical versions of a webpage. It also has a browser extension (Chrome; Firefox) that allows you to see the archived versions with one right click.

MapChecking can help you measure the maximum number of people that can be standing in a certain area. It is useful to understand if someone is lying about a crowd size in a protest, for example.

The CrowdTangle browser extension (Chrome) can help you find out how frequently a link has been shared on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Reddit and by whom. For example, you can see the Facebook pages and groups that are sharing an article or are trying to get signatures for a petition.

If you would like to read more about fact-checking and investigating on social media platforms, this free handbook offers a lot of tips, insights, and case studies.

Fact-Checkers in the Baltics and Abroad

If you are not sure whether to believe a claim or not, often some fact-checkers have already tried to find the answer. Here are some websites of international and local fact-checking organizations.

Baltic resources:

Re:Check by the Baltic Center for Investigative Journalism Re:Baltica

Atmaskots by Delfi.lv

Melu detektors by LSM.lv

Melo detektorius by Delfi.lt

Patikrinta 15min by 15min.lt

LRT Faktai by LRT.lt

Faktikontroll by Eesti Päevaleht

Klikisäästja by Levila

International resources:

Become a Fact-Checker

Did a Human Create This?

Another important question that we already have to answer with increasing frequency is whether a piece of content has been created by AI (artificial intelligence). AI describes tools that perform tasks commonly associated with intelligent beings. Recently, you might have heard about it in the context of a chatbot called ChatGPT or image generators such as MidJourney or DALL-E.

These tools are often used to speed up various time-consuming tasks such as writing e-mails, generating schedules and to-do lists, assisting in coding, and creating visual mood boards for artistic projects. However, they can also be used to create hard-to-detect misleading information at an unprecedented speed.

The AI field is growing rapidly and people who develop tools to detect inauthentic content are still catching up. However, there are a few tools you can use to try to understand whether text you are seeing has been created by AI. You can copy and paste a piece of text into these tools for a rating of how likely it is that the text is AI-generated.

The lengthier the text, the more likely it is that these tools will be able to detect if it has been generated by AI. However, some of these tools have a limit of characters. It is worth inserting the text into all the tools mentioned above instead of just one because some of the tools currently do not detect AI-generated content with high accuracy. For example, Text Classifier by OpenAI, the same company that created ChatGPT, is only able to accurately identify 26% of AI-generated texts in English, as reported by the company. The number is likely lower for content in other languages.

Here is another tool that allows you to check whether an image has been generated by AI:

Resources for Educators – Teaching and Learning with AI

Are you an educator working with Very Verified, involved in media literacy education, or simply curious to learn more about the uses of AI in education? The links below contain useful resources, examples, and information on the current context of teaching and learning with AI both inside and outside of the classroom.

CITE Journal Editorial: ChatGPT: Challenges, Opportunities, and Implications for Teacher Education

Harvard Graduate School of Education: podcast EdCast Educating in a World of Artificial Intelligence; article Embracing Artificial Intelligence in the Classroom

University of Washington Center for Teaching and Learning, ChatGPT and other AI-based tools